Carlos Cruz-Diez is known as the great master of colour. His interest in it goes back to his earliest childhood, to the time when “my grandmother used to serve me breakfast on the white tablecloth where the colours of the glass in the nearby lattice were reflected. Those colours were not painted on the tablecloth, and yet they existed and I played with them”.1

As soon as he entered the School of Fine Arts it was clear to this Venezuelan artist that he did not want to do what had always been done. And so it was that he turned his attention initially towards socially committed art, although he realised at once that that was not his path.

Cruz-Diez took his art out of the studio and into the street, something that was to be a constant feature of his career. He made colourful zebra crossings in Caracas and even a project for the metro in Paris – the city where he lived for much of his life – that could be viewed from the carriages, all with the aim of “creating a visual shock to awaken us from the robotic attitude we submit to when travelling around the city”.

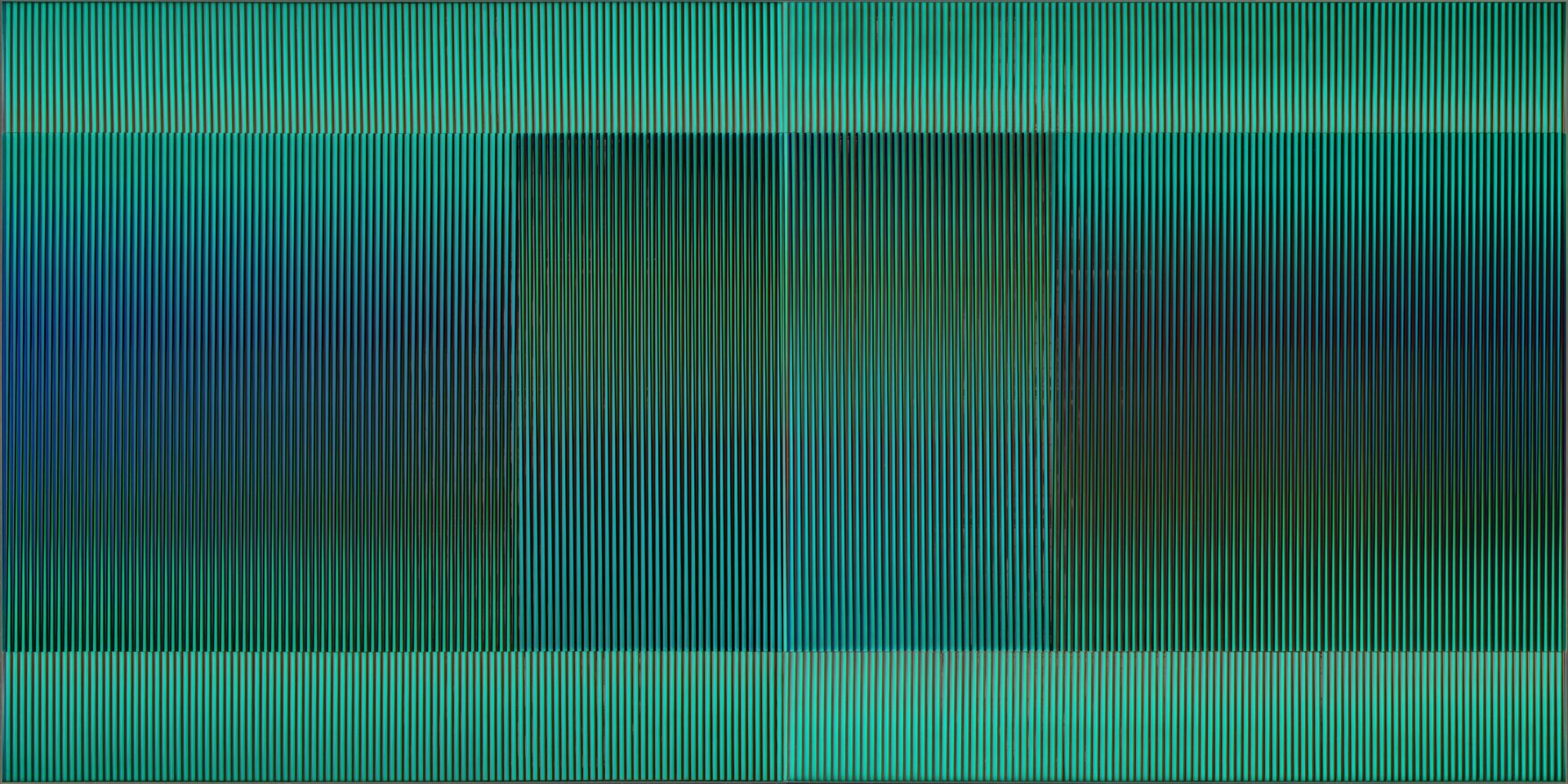

In this way, Cruz-Diez arrived at what is known as kinetic art or optical art. The precursor of this movement was Naum Gabo with his realist manifesto; then came Calder with his mobile sculptures, and finally a whole series of artists who got together in the mid-1950s at the Galerie Denise René in Paris. Among them were Cruz-Diez and his fellow countryman Jesús Rafael Soto. The work of these artists represented a real revolution in the art of the second half of the twentieth century, to the point that the collections of the best museums, such as Tate Modern and the Pompidou, have a room devoted to this movement. With kinetic art, in Cruz-Diez’s words, “art went from being contemplative to being participatory. People abandoned the wall and expressed themselves in space with ‘ambiences’. The multiple was created, so that distribution would avoid only a minority being able to enjoy works”.

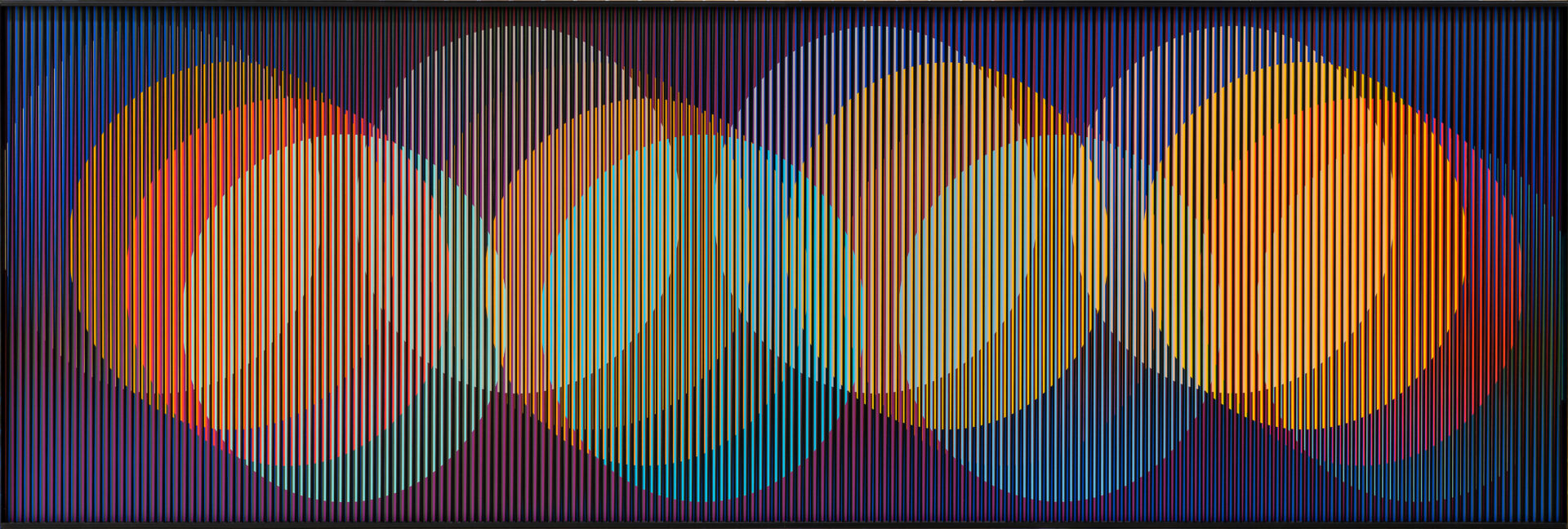

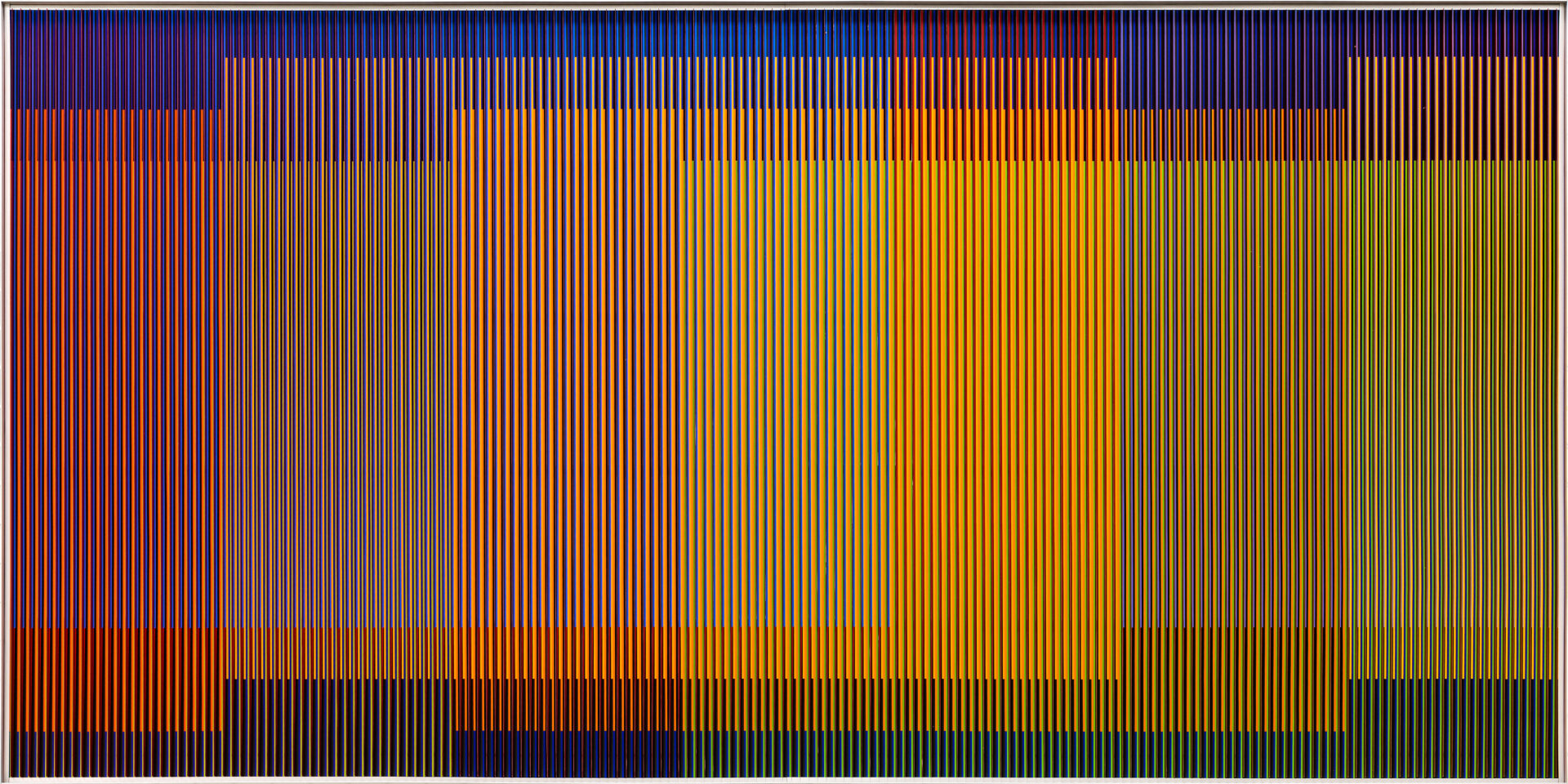

The fact is that this artist considers that his works “are not paintings or sculptures, but ‘supports for events’. I try to highlight the various manifestations of the world of colour. In my works, the colour we see is not the one that has been painted on the support, and people find this amazing and moving”.

The Hortensia Herrero collection presents a wide variety of works by Cruz-Diez in which we can observe his mastery in the use of colour. Outstanding among them is Physichromie 2222 (1988), a piece that the gallerist Denise René kept in her home until she died in 2012.