“I have spent two years imprisoned in an office, where I have made the sacrifice of being unable to admire the great beauties of nature that I love.”1 So wrote a young Joan Miró to his parents, at the age of seventeen, in a letter dated 2 April 1911, at the end of which he announced, with clear determination: “So I am giving up my present life to devote myself to painting.”

Freedom was one of the main watchwords of this artist, who always shunned being pigeonholed in movements such as Cubism, Surrealism or Abstraction and became one of the greatest artists of the twentieth century with his own style.

Like so many artists, Miró began by painting in a figurative manner, but one on which he put his own stamp from the outset. He was trained at the Galí school, which used very innovative methods for the time. As Miró himself explains: “He would tell me to close my eyes, to feel an object, or even a classmate’s head, and then I had to draw from memory – my hands’ memory. Yes, that’s where my sense of volumes and my interest in sculpture came from, even though I didn’t try my hand at sculpture until late. In any case, these nudes are done as much with the experience of touch as with that of the eye!”2

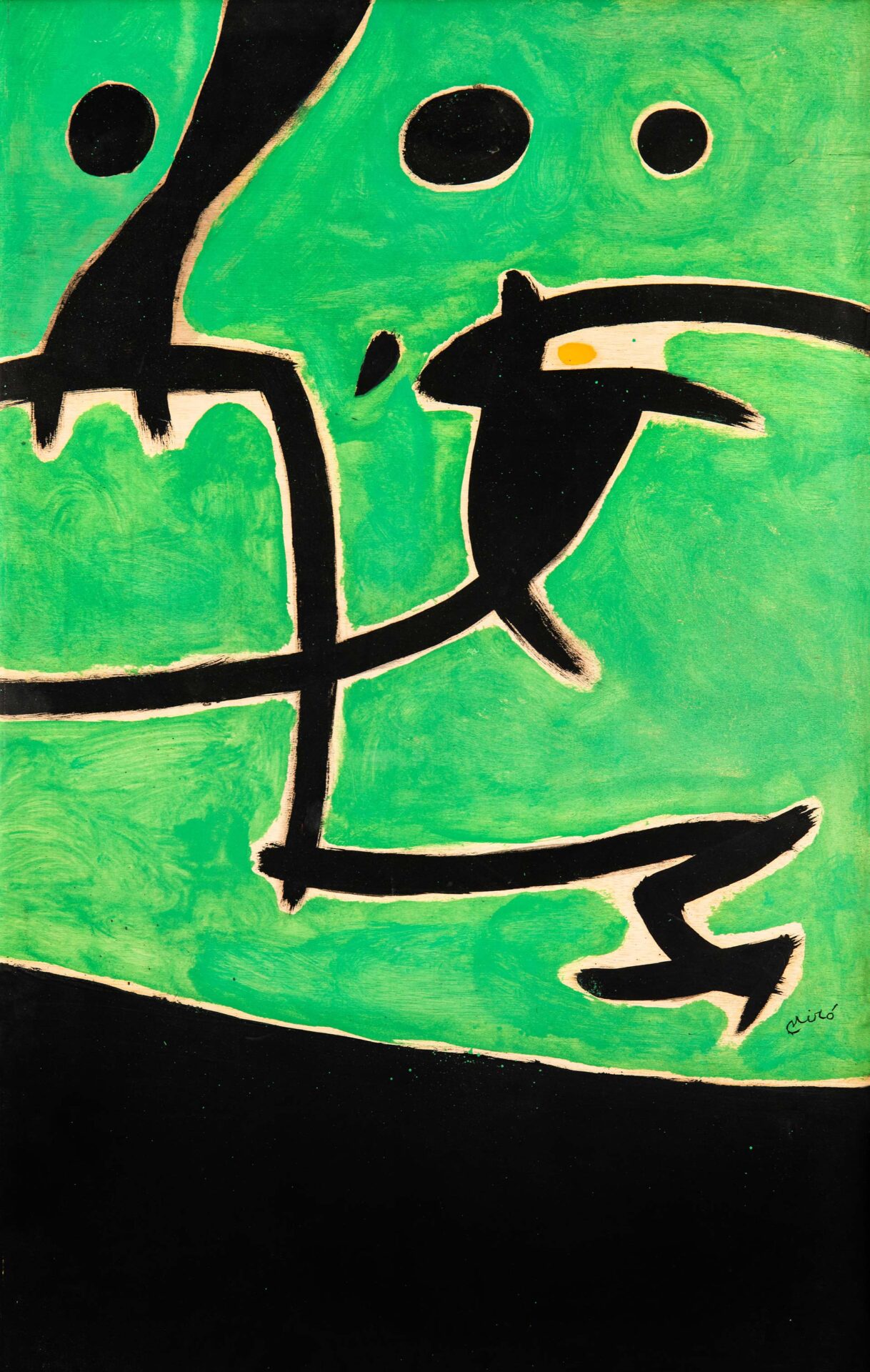

After a brief experience of Surrealism in the 1920s, Miró set out alone on his own path, developing his own visual language. During the 1930s, he created an iconography composed of highly colourful human figures on predominantly dark backgrounds, vividly foreshadowing the prewar atmosphere that was to culminate in the Spanish Civil War.

The year 1941 represented a turning point in Miró’s career. It was the year of his first retrospective at MoMA in New York, which definitively cemented his international prestige and influenced the generation of artists who were to create American Abstract Expressionism, such as Arshile Gorky, Mark Rothko, Robert Motherwell and Jackson Pollock. In this period, Miró had already consolidated a painterly language of his own, integrating the whole picture space into a single surface in which form and content coalesced.

Although Miró had made occasional forays into sculpture during the 1920s when he was involved in the Surrealist movement, at that time it was more a question of hanging objects on the paintings to create a third dimension. In the sixties and seventies, however, sculpture emerged as another artistic discipline within his wide-ranging repertoire. Miró began by modelling ceramics and casting them in bronze and ended up giving new life to the objects that inhabited his studio. With these, Miró constructed new figures, which he assembled and cast in bronze, painting over them in many cases in a wide range of colours.

Miró thought of his studio as a garden, and as he himself explained: “I’m always working on a great many things at the same time. And even in different fields: painting, printmaking, lithography, sculpture, ceramics.”3

Miró’s work can be found in the collections of the world’s leading museums and there are three Miró foundations (Barcelona, Palma de Mallorca and Mont-roig) open to the public where his work can be studied in depth.

The Hortensia Herrero collection has two works by Miró: a watercolour of the 1930s and an oil painting from the final stage of his career.