Olafur Eliasson achieved recognition very early in his career. The intervention entitled Green river (1998) helped to make his work known in cities such as Stockholm, Bremen, Los Angeles and Tokyo. This project involved dyeing the rivers of these cities green, a colour usually associated with healthy things but that in a river can be interpreted as something toxic or polluting. He carried out this action in complete secrecy and without warning, with a harmless, water-soluble fluorescent dye called uranine. The idea was to observe people’s reactions, which ranged from a police investigation in Tokyo to the indifference of the citizens of Los Angeles.

After this and other public works deployed in cities around the world came the project that sealed his reputation as an artist and popularised him among the general public: The weather project (2003), that great sun he installed in the Turbine Hall at Tate Modern, where people came to lie down as if on a beach of the future.

Eliasson works with materials as varied as ice, wood, glass, moss and cacti. Investigating new materials is an important part of the work of his large studio, which, at the busiest times, has more than a hundred workers. This huge team is led by a single person, driven by something as simple as curiosity. “Curiosity is very important in my work, but it’s not something that can be forced”, he explains. “When I notice that I’m losing my curiosity, I feel I have to slow down my work.”1

Eliasson has produced exhibitions and projects both in open spaces and in historical buildings, as well as in neutral museum rooms (known as “white cubes”). One of his best-known interventions in public places consisted of installing four enormous waterfalls in various locations in New York City. “I think it’s important to exhibit everywhere, but exhibitions in open spaces are more accessible to the public, because many people think that galleries and museums are elitist or perhaps boring.”2

Hortensia Herrero commissioned Olafur Eliasson in 2020 to produce a site-specific work for the future Hortensia Herrero Art Centre in Valencia. For this purpose he was offered a passage on the second floor leading to a small room with no exit, so visitors have to retrace their steps. Eliasson designed a tunnel, which he entitled Tunnel for unfolding time (2022), in which the visitor can see 1,035 pieces of glass, each of a different size and design and in all the colours of the rainbow, but when you look back all you can see is a black tunnel. As Eliasson himself explains: “I made a tunnel for the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art called One-way colour tunnel (2007), which was, in a way, the first seed of the ideas for this tunnel. This one is more ambitious and I think it’s much more developed in terms of how it accommodates or receives people. I wouldn’t say it’s more generous in that respect, but it does have more to offer. It’s denser, and this idea that when you pass through it, it seems to open up, means that perhaps it’s stretching out more. And then it plays with the idea that it’s very different depending on which way you go.”3

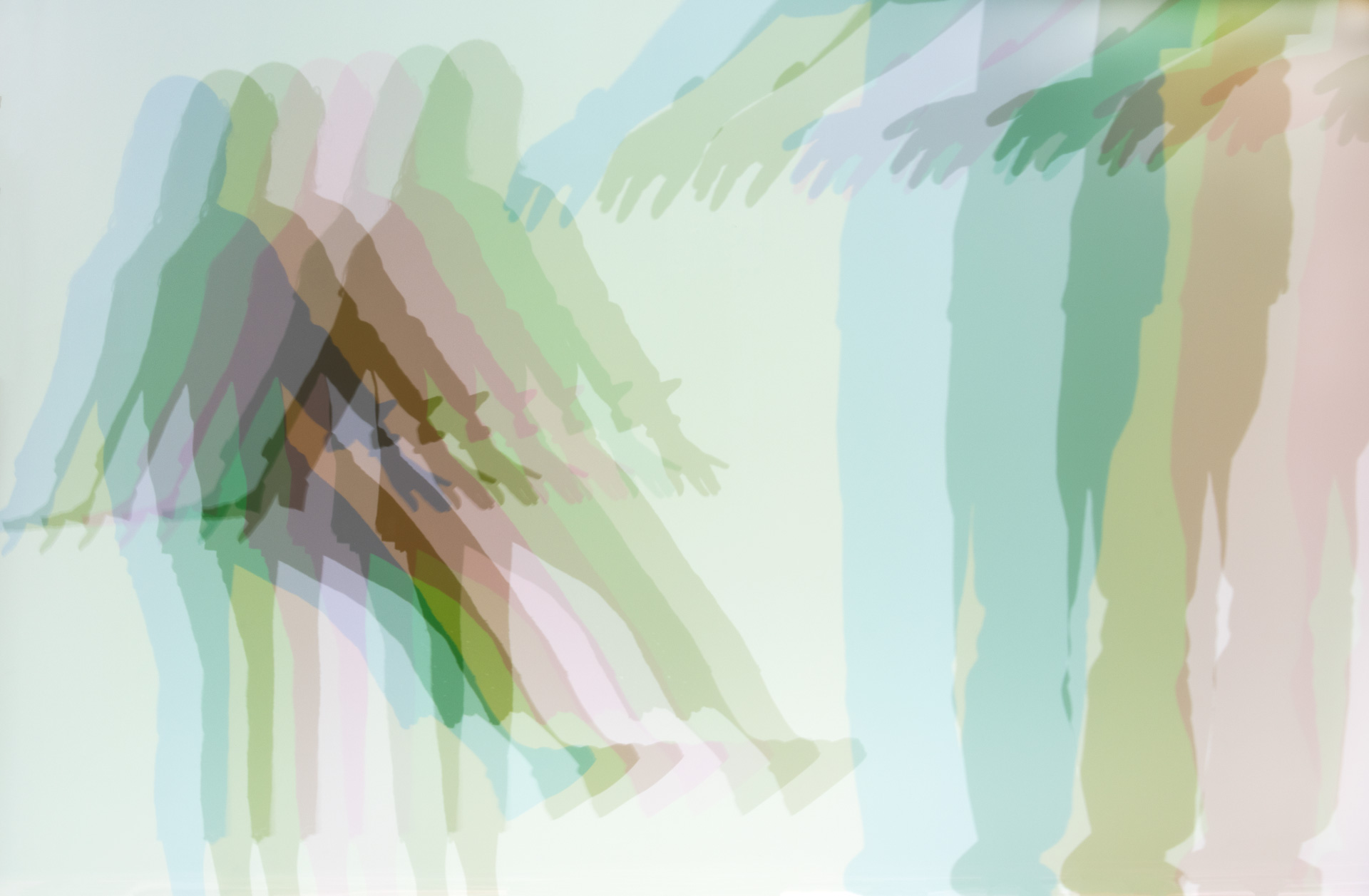

The Hortensia Herrero collection has another large installation by Olafur Eliasson, Your accountability of presence (2021), a work in the same vein as the one entitled Your uncertain shadow (colour) (2010), which Hortensia Herrero had the opportunity to see in the exhibition that Tate Modern devoted to Eliasson in 2019. In both installations, visitors see their silhouettes projected on the wall in a wide range of colours, creating a real play of optical effects in which movement takes on a central role.

Other works by Olafur Eliasson in the collection are The space before the idea (cyan, blue, cobalt, cerulean) (2018) The round corner (18°) (2018).